The Galaxy’s Most Common Stars May Be Missing a Key Ingredient for Life: Long-Lived Moons

ETAMU astrophysicist explores why many alien worlds may lose their moons—and what that means for life beyond Earth.

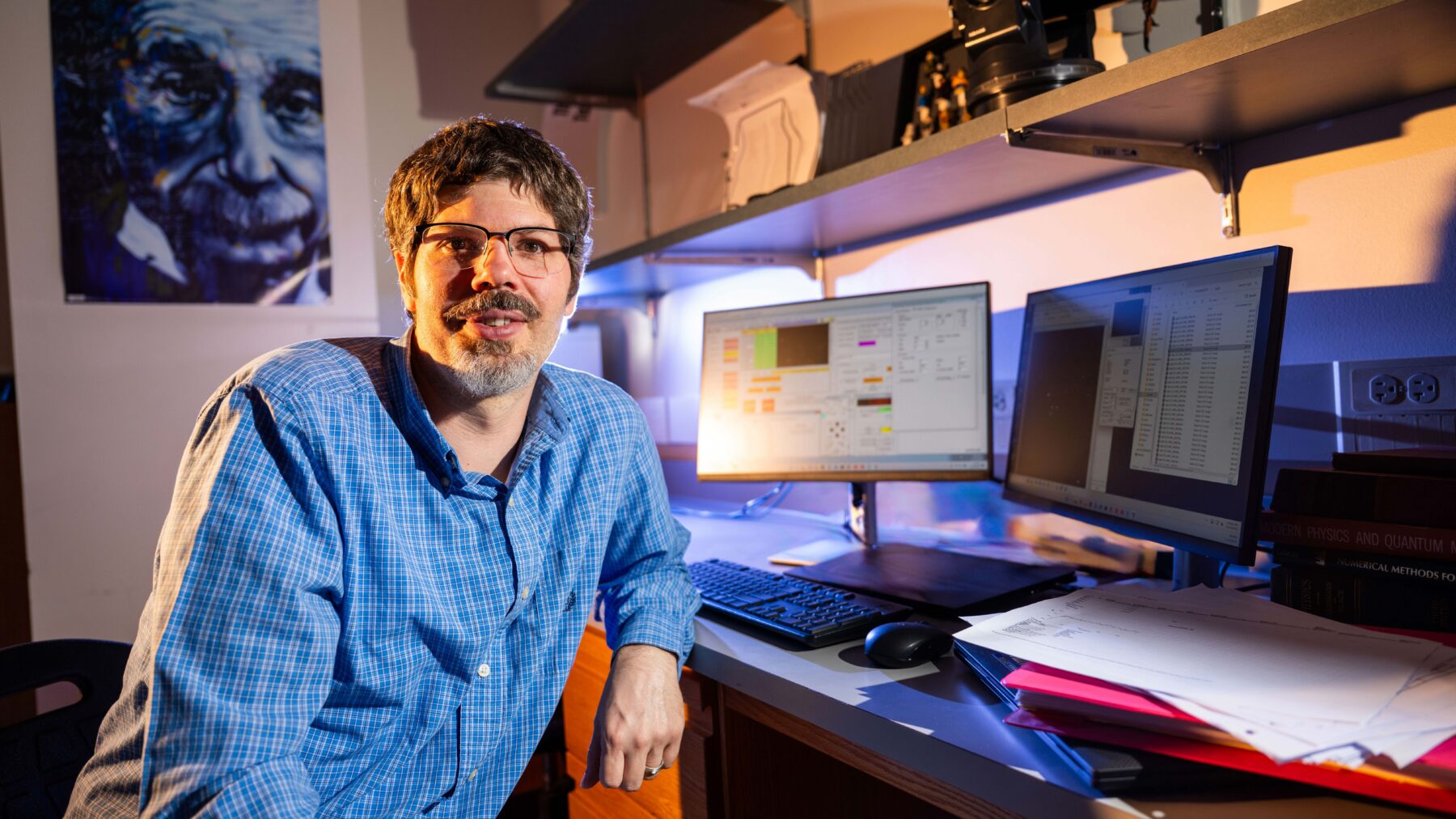

Most stars in our galaxy are small, cool M-dwarfs—the kind astronomers often look to when searching for planets that might host life. But new research from East Texas A&M University suggests these worlds may be missing something important: long-lasting moons. Dr. Billy Quarles, an assistant professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy, recently published a study in The Astronomical Journal showing that moons around M-dwarf planets may not survive long enough to help stabilize the planet or support early conditions for life.

The discovery could reshape how scientists search for truly Earth-like worlds elsewhere in the universe.

The new paper builds on momentum from Quarles' earlier contribution to the discovery of a potential planet in the nearby Alpha Centauri system, a project that highlighted East Texas A&M's growing role in modern astrophysics. Now, his work turns toward the question of whether planets around the Galaxy's most common stars can hold onto their moons long enough to support conditions that might resemble Earth. The answer, according to Quarles and his colleagues, may have profound implications for the search for life in the universe.

To better understand the study, and what it means for students interested in astronomy, physics or planetary science, we spoke with Quarles about exomoons, tidal forces and why our own Moon may be more unique than we realize. The following is our conversation.

How did you get into astronomy?

I grew up in the country, where the night skies were incredibly dark. Being outside, especially through Boy Scouts, gave me a natural curiosity about what was up there. I also came of age in the early '90s, when everyone was watching “Star Trek: The Next Generation” on Saturday nights. That opening sequence—with all the planets—really sparked my imagination and made me think about worlds beyond our own.

In high school I did well in science and math, and my sister had once planned to study black hole physics. She ended up choosing a different path, but her interest pushed me to consider astronomy more seriously. I didn't know exactly what part of astronomy I wanted to study until graduate school, when I realized I loved working on planets, moons and complex star systems. My path wasn't a straight line, but eventually I found where I fit.

What first drew you to study moons outside our Solar System, and what fascinates you about them?

When I started my Ph.D. around 2008, I noticed a researcher who proposed using Kepler Space Telescope data to search for exomoons—moons orbiting planets outside our Solar System. I thought the idea was impossible, so I went down a rabbit hole trying to prove him wrong. Instead, I discovered the idea actually made sense.

At the time, Kepler was finding new planets constantly, and it felt natural that moons would be the next big discovery. I met that researcher, Dr. David Kipping, in 2012, right after I defended my dissertation, and I honestly believed he'd find the first exomoon within a year. That didn't happen, although he did find a couple of promising candidates and eventually invited me to collaborate on one of them.

What fascinated me, and ultimately motivated this new paper, was that observers kept searching for moons around M-dwarf stars but weren't finding any. We wanted to understand why. Our research shows that, in many of these systems, large moons simply aren't expected to survive long enough to be found.

Give us an overview of the paper you worked on that is being published in the Astronomical Journal.

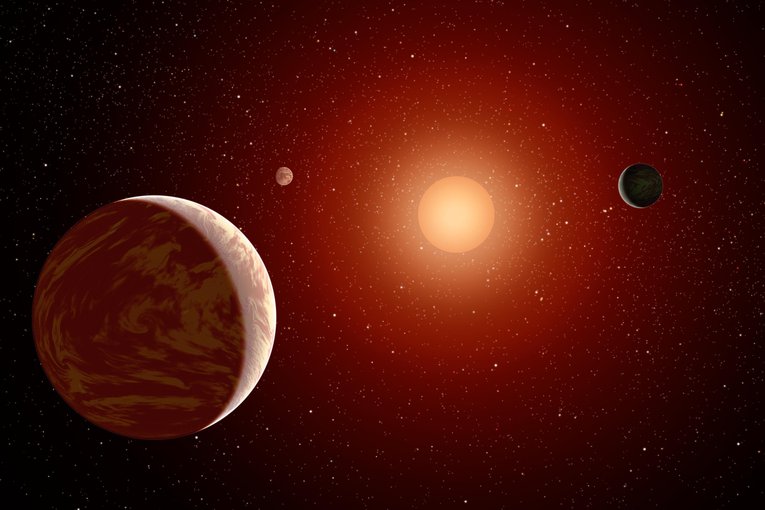

The paper brings together a few important ideas. At first glance, M-dwarf stars seem like ideal places to search for exomoons because their habitable-zone planets orbit quickly. Faster orbits mean more transits, giving astronomers more opportunities to spot a moon passing just ahead of or behind its planet.

But what's good for observers isn't necessarily good for moons. When a planet orbits very close to a small star, the star's tidal pull becomes extremely strong—much stronger than anything in our own Earth–Moon system. Here on Earth, the Moon produces about twice the tidal force of the Sun, which slowly pushes the Moon outward. If you moved that same setup closer to the star, the star's tides would become hundreds or even thousands of times stronger.

Those powerful tides act like an engine that pushes the moon outward so quickly it eventually becomes unstable and escapes. We expected this might shorten a moon's lifetime from billions of years to perhaps one billion. Instead, our simulations show that around most M-dwarfs, large moons survive only 10 to 100 million years.

That's important because life on Earth took far longer to develop. So even if habitable-zone planets exist around M-dwarfs, they probably lost their big moons long before life ever had a chance to begin.

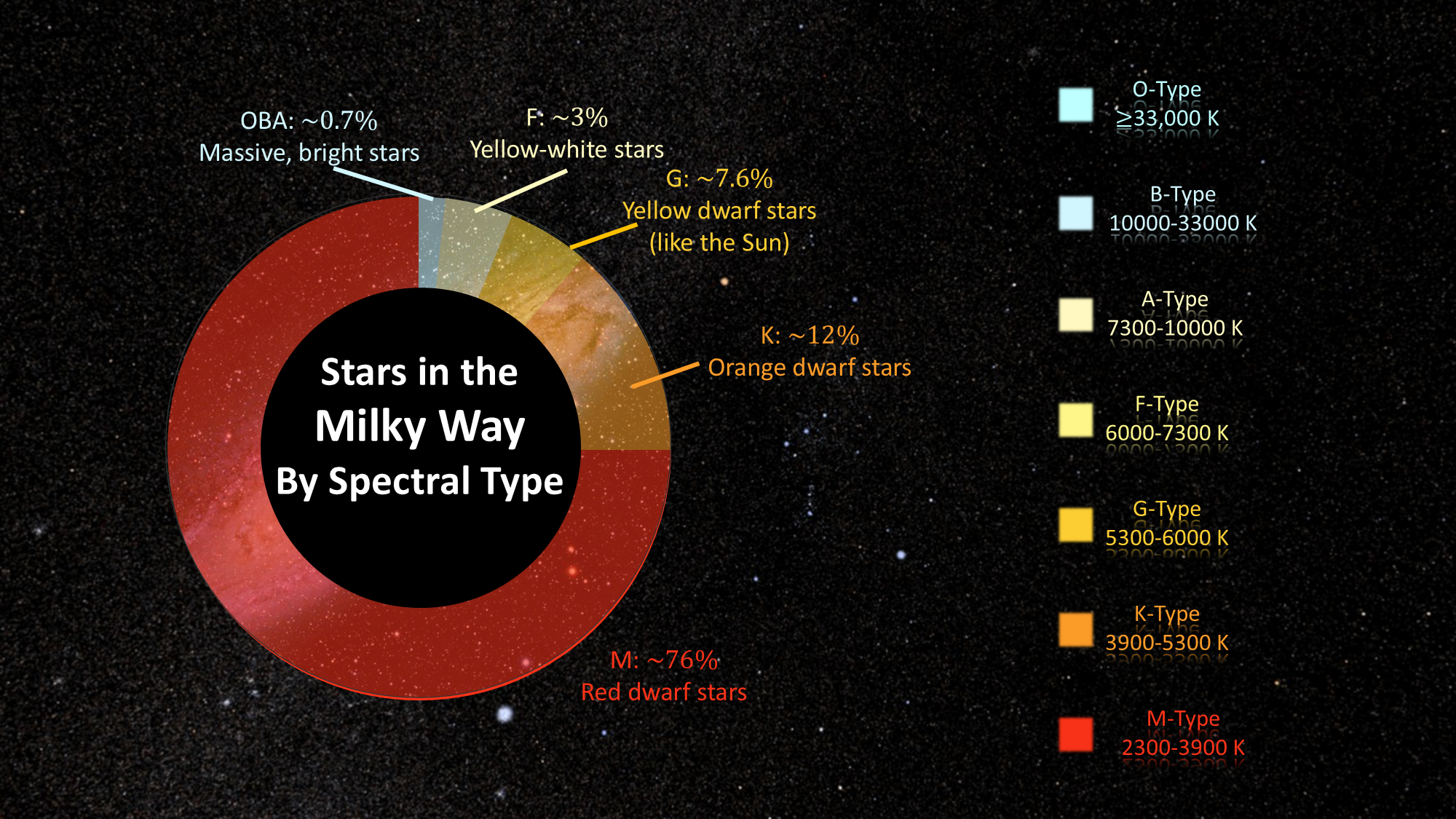

What makes a star an M-dwarf star?

Stars are classified by their surface temperature. Our Sun is about 5,800 Kelvin, but M-dwarf stars range from roughly 2,800 to 4,500 Kelvin. They're cooler, so they emit less light—think of a campfire that burns lower and dimmer.

Because they're dimmer and smaller in size, any habitable-zone planet has to orbit much closer to stay warm enough for liquid water. M-dwarfs also happen to be the most common stars in our Galaxy. About 75% of all stars formed are M-dwarfs, and we expect a similar ratio across the universe.

Why does your finding—that planets around M-dwarf stars probably can't keep big moons for long—matter for the search for life in the universe, and what would losing a moon mean for a planet like Earth?

This result matters because large moons may play an important role in making a planet truly habitable. Some scientists think Earth's early tides—driven mostly by the Moon—helped create the cycles of drying and re-wetting that allowed complex chemistry, and possibly life itself, to begin. The Moon also stabilizes Earth's axial tilt. Without that steadying influence, a planet's tilt can swing wildly over time, as it does on Mars, shifting from nearly 0 degrees to as much as 60 degrees. Those kinds of swings can radically alter seasons, temperature patterns and the long-term stability of a planet's climate.

If a planet loses its moon, the effects show up quickly. On Earth, tides would weaken dramatically, disrupting coastal ecosystems and the fishing industries that depend on predictable tidal cycles. Many insects, birds and nocturnal animals also rely on moonlight—especially during the full moon—to navigate or time certain behaviors. Losing that constant light source would unsettle those ecosystems before they could gradually adapt.

That's why the study is important: a planet can sit comfortably in the habitable zone, but without a long-lived moon, it may struggle to stay habitable at all. The changes on Earth would be dramatic.

But without a Moon, there would be no more full moon, thus no more werewolves.

Right, no more werewolves.

Was there a moment in the research where something unexpected showed up in the data?

At first, we noticed a mismatch between two different ways of running the models. One method calculates the forces at every tiny time step, while the older method averages the forces over an entire orbit of the moon. Those two approaches should agree, but they didn't—the high-precision model showed the moon migrating much faster than expected.

It turned out the issue was a small error in the tidal code we were using, a missing factor of one-half. The code is maintained by Dr. Daniel Tamayo at Harvey Mudd College, not by us, and once we identified the discrepancy, we corrected for it and recalibrated our results.

Even after the fix, the moons were still disappearing much earlier than expected. We had predicted lifetimes of about a billion years, but the simulations showed they were vanishing far sooner. That's when we realized mean-motion resonances were at work.

A resonance acts like pumping your legs on a swing—it gives a regular “push” that builds over time. In this case, the star was pushing the moon's orbit, making it more elongated. That closer approach to the planet greatly strengthened the tidal forces, which explained why the moons were being lost so quickly.

When the moon ceases to exist or separates from the planet, what actually happens?

Once a moon becomes dynamically unstable, it simply escapes the planet's gravity. In many cases it doesn't leave the star system—it just remains in orbit around the star. Those bodies have been nicknamed ‘ploonets' because they started as moons but end up acting like small planets.

There's also a chance the escaped moon could collide with another planet in the system. Many M-dwarf systems have multiple planets packed closely together, so an outgoing moon has several potential targets. Either way, once the moon separates, it no longer behaves like a moon at all.

Since the study suggests that big moons are rare around these stars, what does that mean for the chances of finding truly Earth-like worlds elsewhere?

When missions like Kepler looked for Earth analogs, they were searching for an Earth-sized planet on a one-year orbit around a Sun-like star. But Sun-like, or G-type, stars are actually pretty rare—only about 8% of stars fall into that category. In contrast, around 75% are M-dwarfs.

If large, long-lived moons can't survive around M-dwarfs, then we've effectively ruled out three-quarters of all stars as places where an Earth-Moon system like ours could exist. That doesn't mean life is impossible elsewhere, but it does narrow the field. If having a large moon is one of the conditions that helps life emerge or remain stable, then Earth may be more unusual than we thought.

Even if life is a one-in-a-billion occurrence, there are still billions of stars. But removing 75% of them from consideration does make truly Earth-like worlds rarer in the universe. In turn, that makes the search for life more complex.

Tell us about your co-authors and how the collaboration worked.

My co-authors are all from the University of Texas at Arlington. The last author on the paper was actually my Ph.D. co-advisor, Dr. Manfred Cuntz, so this project brought things full circle. The lead author, Shaan Patel, defended his dissertation on Nov. 11, so he'll soon be Dr. Patel. This study formed a major part of his Ph.D. work. He had already published papers on moon dynamics, including one focused on the planet K2-18b, and this new project expanded that work to M-dwarf systems in general.

Our third co-author, Dr. Nevin Weinberg, is a newer faculty member at UTA and an expert in tidal interactions, specifically between stars and hot Jupiters. His experience helped us anticipate how our models should behave and interpret the results correctly.

So the collaboration worked well because each of us brought different strengths: experience with moon dynamics, expertise in tidal physics and the practical drive of a graduate student pushing toward the next step in his career.

For students who are curious about space and want to study planets, what kind of classes or skills would you recommend they focus on?

Students interested in space should focus heavily on math and physics. In the U.S., it's actually uncommon to earn an undergraduate degree specifically in astronomy. Most astronomers and planetary scientists start with degrees in physics or engineering and later move into space-related fields. My own Ph.D. is in physics and applied physics, not astronomy, simply because those programs overlap so much.

Here at East Texas A&M, we offer courses like Life in the Universe and Solar System Science, which introduce students to planetary and astrobiological topics. As our program grows, we're also exploring the possibility of an upper-level astrobiology course.

Astrobiology itself is very broad—some researchers come from biology, others from chemistry, physics or engineering. The field brings together multiple sciences, so having a strong foundation across several areas is a real advantage.

As researchers continue exploring the physics of distant worlds, studies of how moons form, migrate and disappear around other stars highlight how much there is still left to uncover—and how institutions like East Texas A&M are helping push that frontier forward. For students interested in exploring the cosmos, Dr. Quarles' work offers a reminder that big discoveries often begin with simple questions and a willingness to follow the evidence wherever it leads.